This is another piece from my defunct film website. Written way back in 1998, before science fiction fandom became ‘mainstream’

This is another piece from my defunct film website. Written way back in 1998, before science fiction fandom became ‘mainstream’

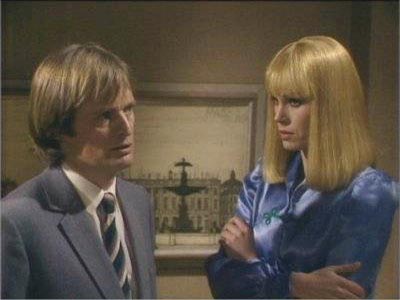

I first came across Sapphire and Steel, an obscure British science fiction series made in the early 1980s, while I was browsing through a mail order catalogue in the late 90s. I read the description: ‘a strange and fascinating show – definitely something different’. Always on the lookout for the unusual, I ordered volume one expecting no more than the usual B grade offering that is unfortunately usually the rule when it comes to television science fiction. I was more than pleasantly surprised when I discovered something that actually did match the catalogue description. By the end of Adventure 1, I was hooked and submitting my credit card to a severe workout, I ordered the remaining 5 Adventures on tape. At the same time as I was watching the series I was also reading the works of Antonin Artaud. The combination was quite extraordinary – the television series echoing a number of Artaud’s insights into the radical disjunction between words and things.

The piece below probably won’t make a lot of sense unless you have seen the series. An overview and information can be found on the Wikipedia page for the series. You might also like to have a look at an earlier post on Sapphire and Steel on this blog.

Introduction

One of the most striking features of Sapphire and Steel is the fact that it offers so few explanations and so few obvious answers. Not only do the backgrounds of the characters and events remain mysterious, but the most ordinary objects take on completely unexpected meanings. A feather pillow becomes a dangerous vengeful creature, a nursery rhyme the physical manifestation of an evil force, a travel chess set a terrifying weapon and gateway to time and other dimensions. Nothing can be taken for granted in this series.

This indeterminacy of meaning and explanation encourages viewers to actively imagine and speculate, to create their own very personal interpretations, to face particular types of limit experiences and the possibility of other worlds using the structure of their own psyches and imaginations. The whole series is an invitation to think beyond it, to engage in difficult confrontations and experiments in thought and imagination: it is an open challenge to question accepted visions of social and physical reality without this ever being a stated or obvious intention of the series. Thus, even if the series is a relatively short one, it offers far more fodder for creative discussion and invention than do a number of other longer running productions with more elaborately developed and codified world views and with far more visible signposts as to their intentions.

This article will take up the challenge and provide speculative answers to questions raised by Sapphire and Steel. These answers are by no means intended to dispel the original mystery and indeterminacy: their purpose is rather to open further opportunities for debate, speculation and imagination… And what better place to start than with the most obvious question?

Who are Sapphire and Steel?

Ostensibly, Sapphire and Steel are two operatives who are sent to earth to prevent or repair ruptures in the strictly ordered fabric of time, to maintain the integrity of past, present and future. These disruptions to time are initially assessed by ‘investigators’ who are never seen, who then brief and send in ‘operatives’ such as Sapphire and Steel. ‘Specialists’ are sent to the scene at a later stage to undertake any specialised tasks that operatives are unable to perform. This rather summary information emerges in a somewhat fragmentary and incidental manner at various points throughout the series in conversations between the two main characters, with humans and with the two specialists Lead and Silver. This is what Sapphire and Steel do but what sort of beings are they and where do they come from?

Are Sapphire and Steel alien or human?

This question is worth asking for a number of reasons, especially in view of a regrettable tendency in many American science fiction series in particular, to make most of the principal ‘alien’ characters semi-human at least in some way. In the original Star Trek, the alien Spock is only ‘half’ Vulcan, the ‘other half’ is human. The crew of the Enterprise in the next generation of Star Trek features a half human betazoid, a Klingon brought up by human parents and an android engaged in a life long quest to become human. And in conversations between the alien Q and Captain Picard we see the standard rhetoric that for all their faults and weaknesses, humans have ‘special qualities’ unique in the universe. In the other two offshoot series of Star Trek, Deep Space 9 and Voyager, the resident aliens are even more tedious and predictable than the humans. It might be argued that Babylon 5 is slightly better on this score – but the writer Joe Michael Straczynski still cannot resist the temptation of mixing human with one of the more ‘noble’ alien races, the Minbari. The Vorlons have also demonstrated suspicious fraternising tendencies – of a kind at least – in their use of figures such as Jack the Ripper to do their dirty work for them. Neither can Straczynski resist the ‘unique quality of humans’ school of rhetoric. Even in that post gulf war expression of military paranoia Space Above and Beyond, it transpires that the evil and hideous aliens had somewhere back in depths of time originated from the planet earth. British science fiction tends to perform a lot better on this front, but not even the Paul McGann version of Doctor Who, it seems, can survive a trans Atlantic regeneration intact. In a truly horrifying gesture, undermining a fine tradition of long standing – the completely alien doctor suddenly acquires a human parent, thereby ‘explaining’ his long term interest in earth. Is it really necessary to be part of a species or culture to show some interest in it? Why is there such a determined and rigid obsession with rendering the entire universe human in American science fiction? This is indeed a fascinating problem and certainly one worth exploring at more length. As some writers have suggested all of this is perhaps a thinly disguised reflection of the USA’s current imperialist stance with regards to cultures which are not American.

In such a human centred universe, Sapphire and Steel are a welcome arrival. They are clearly alien ‘in the sense of being extraterrestrial’ as Steel confirms in as many words in Adventure 5. Attempts to appropriate anything like a ‘human past’ for Sapphire and Steel have been firmly but politely rejected by the writer of the series P.J. Hammond in an interview with Rob Stanley.

How do Sapphire and Steel differ from humans?

As P.J. Hammond remarks, if Sapphire and Steel are more than ‘mere mortals’ they are still to some extent ‘mortal shaped’. They both speak English (that well known universal tongue!) and appear to have a human form, but for all this, the nature of their relationship to their bodies is uncertain. The opening animation, which shows glittering spheres representing a number of different ‘elements’, might suggest that their human shapes are something they adopt for the sake of convenience. Yet in Adventure 4, Sapphire, addressing a creature which changes its face at will, states that she and Steel have only ‘one face’. Their bodies can also be damaged as various incidents with absolute zero temperatures, barbed wire, knives, imaginary swans and attempts at strangulation indicate, but at the same time they appear to have remarkable powers of regeneration. In Adventure 3, the technician Silver refers in passing to a faculty of ‘instant reduplication’ which might explain these recuperative powers, but even this, it appears, is fallible. It is the failure of this faculty which results in his disappearance into his own past at the hands of the changeling, and he also mentions when threatened by the transient beings, that he would not survive in the Triassic period. One thing is clear, however, the relation Sapphire and Steel and similar beings have to their bodies is quite different to our own.

The fact that they are not human is apparent right from the outset. Almost as soon as they walk in the door in Adventure 1, we see Sapphire’s eyes turn a brilliant shade of blue as she briefly investigates the situation. The two operatives are able to communicate telepathically with each other and have obviously arrived at the house through some means of transport other than the more conventional ones of car and boat, which as the boy explains can be heard coming for miles in that isolated spot. Adventure 2 shows them teleporting and they make more use of this power in subsequent adventures. A marvellous but very brief scene in Adventure 5, a fine example of Shaun O’Riordan’s direction, offers perhaps the closest thing on film to a subjective view of teleportation. The background behind Steel fades to black and we see him in a closeup shot turning to face a new environment. Other series, notably Blake’s 7, Star Trek: The Next Generation and The Tomorrow People have all attempted subjective views of teleportation, but where Sapphire and Steel is radically different is in the fact that the two main characters do not require technology to assist them. Neither does Steel signal in any way his intention to teleport. Like many other scenes in the series it remains mysterious and there are no obvious indications as to how the viewer is meant to interpret it. As a result, this sequence arguably works far better than other more detailed and elaborate efforts to convey what teleportation might actually feel like.

It would also appear that the two agents have a very long lifespan in our dimension. In Adventure 1, they reveal that they dealt with a problem on the Marie-Celeste and indicate in Adventure 4 that the passage of hundreds of years is of little consequence to them. They have other powers as well: the enviable ability to change clothes and hairstyles in the blink of an eye, for instance. Sapphire parades a number of outfits in front of Rob in Adventure 1 and both she and Steel waste no time changing into their thirties costumes in Adventure 5. In addition, they both possess telekinetic abilities – very handy when it comes to locking and unlocking a variety of doors and turning off record players! Sapphire is able to ‘take time back’ for limited periods, to ascertain the age and nature of objects and to access historical data of both a general and individual kind. Steel can reduce his body temperature to just above absolute zero and he is very strong both psychically and physically and often acts as a kind of anchor for the more volatile Sapphire. Both of them appear to have hypnotic powers of persuasion over humans which they can exercise by a touch or a gaze but they only seldom choose to do so.

But these things aside, what most marks them as alien is the way they respond to situations and the kind of remarks they make about humans. They clearly regard humans as very different from themselves and Steel, in particular, frequently expresses a mixture of exasperation and puzzlement over human behaviour and customs. First impressions of both Sapphire and Steel are of a rather chilly and impersonal detachment. Steel is frequently abrupt to the point of downright rudeness and while Sapphire might initially appear more gracious, she is certainly a match for Steel when it comes to coolness. While shaking hands and making polite conversation with Tully, she is in reality communicating a cold scientific analysis of her subject to Steel.

Neither of them react in quite the ways we would expect people to react in similar situations, yet it is not a question of that other well-worn science fiction cliché: the aliens-who-know-no-emotions in the face of a unique, and as such, admirable, human prerogative. It is more a question of a different emotional response – one that does not always match our well trained social expectations. There is, for example, a definite, if very understated, romantic attachment between Sapphire and Steel, but the way this is played out is by no means conventional, leading some viewers to wonder whether their feelings for each other are real or indeed, whether they exist at all. Again, nothing is at it appears to be: the coldly distant demeanour of both characters is continually belied by their actions in taking the most extreme risks to save humans at every possible opportunity. If Tully is sacrificed, it is to save hundreds of human ghosts. Both Sapphire and Steel endanger themselves to help the woman in Adventure 6, Steel explaining to Silver that it is their duty to do so. Indeed, it is perhaps as a direct result of this concern that they are caught in the trap at the end. Both agents, in fact, display strong, if strictly controlled, emotional responses in relation to humans on a number of occasions. For example, when Steel realises that he has almost stabbed a baby and when the creature in Adventure 4 burns two people alive in a photograph, he is clearly upset. There are numerous other examples. But all these observations do no more than raise further interesting questions, further fodder for speculation. They merely begin to scratch the surface of the hundreds of possible questions that one might ask…

Links to other Sapphire and Steel pages

Revisiting Sapphire and Steel

Sapphire and Steel. Sci Fi Freak site

Page on TV Tropes

Stephen O’Brien SFX magazine

Page on British Horror Television

An Extract From Mark Fisher’s Ghosts Of My Life. A reflection on Sapphire and Steel